According to Wikipedia, Reinforcement learning (RL) is an area of machine learning concerned with how intelligent agents ought to take actions in an environment in order to maximize the notion of cumulative reward.1 . This sentence both says a lot, and at the same time tells very little. In layman’s terms, reinforcement learning is teaching a worker (the agent) to learn how to perform a task on its own. But how does an agent learn on its own? We leave the agent to its own devices. The agent is free to take whatever allowed action it wants and over time it may stumble onto a solution. We incentivize good solutions by giving the agent a task: maximize reward. This reward is specified by the programmer (a.k.a. us). Oftentimes we reward the agent for coming to a solution and apply penalties to longer solutions to encourage good solutions.

Let’s first set out a few definitions:

- Agent: The entity that is taking actions. In this case the agent is our algorithm that is trying to learn the optimal solution. A real world example would be a chess player.

- Environment: The world the agent interacts with and is not in complete control over. The agent’s environment may not only be its outside world. For example, a robot dog’s environment not only consists of its surroundings, but also of its battery. After all, if our robot dog went outside in the yard and its battery died right before a snowstorm, it would be rather inconvenient.

- State: The current condition of the environment.

- Policy: The way an agent behaves in a certain time or position. In a more mathematical sense this is the mapping from the perceived state(what the agent sees) to an appropriate action.

- Reward: This is the value we aim to maximize in the reinforcement learning problem. It is a measure of the immediate desirability of a state.

A simple example would be that of a chess position. The players are the agents, the chess board the environment and the reward victory. A move is an action, and the resulting chess position the state after move t.

It should be noted that we are only rewarding final outcomes. We rarely, if ever, evaluate intermediate states or positions on our own, this is for the agent to figure out. This is primarily because human evaluations are often inaccurate. Give 10 people a difficult chess position and they may have wildly varying opinions on what’s best to do. We let the agent determine the desirability of a state in terms of its long term prospects, i.e. its value.

Strictly speaking, values are predictions of future rewards. It is these values the agent continuously estimates, evaluates and re-evaluates. For the best course of action, the agent picks the actions with the best values in what we call a greedy manner.

To summarize, the key feature of a reinforcement learning algorithm is its ability to interact with the environment, take feedback from it, and learn. Like a toddler learning how to walk, the algorithm(agent) continuously tries different actions until it finds the best(most rewarding) one.

Supervised, Unsupervised and Reinforcement Learning

Supervised vs Reinforcement Learning

Supervised learning is the process of learning from a set of labeled data. The algorithm’s job is to extract patterns and information from this labeled training data and generalize it. This simply does not work in complex, interactive situations. Labeling is also impractical in such problems as rewards are often delayed and the number of possible states numerous. Here, reinforcement learning algorithms can learn from experience.

Unsupervised vs Reinforcement Learning

Unsupervised learning attempts to cluster unlabeled data into groups. While exploring unseen structures is also relevant to reinforcement learning, the overarching goal is different. Reinforcement learning is goal-driven and reward-oriented.

Connect-4

Let’s play a game of of Connect-4. Two players take turns to drop checkers on an grid, with the goal of connecting four checkers in a row. The first player to do so wins. Each player only has 7 possible actions each turn, i.e. the column to drop a checker on. Such a simple game can lead to 4,531,985,219,092 positions2! This makes classical methods such a minimax game theory, numerical optimization and dynamic programming methods3 unfeasible (these methods remain unfeasible for simpler games like tic-tac-toe).

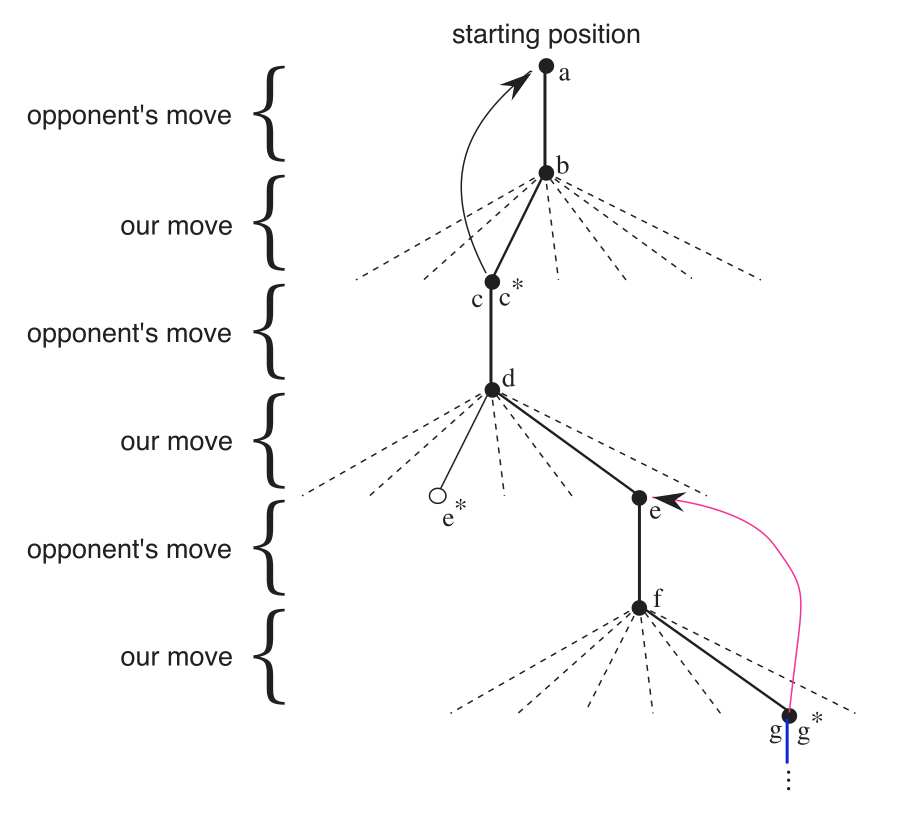

We would teach our agent to learn this game in the following way. First we set a table of numbers corresponding to the possible moves from each position (we only hold a small subset of these positions in memory at any given time for practical reasons). Each of these numbers correspond probability of us winning from that state, i.e. its value. We play thousands of games against the opponent. To select our moves(actions), we look at the resulting state from each move and look up their values from the table. Most of the time our agent plays greedily, only selecting the best values in the table. From time to time our agent will select random, sub-optimal moves. These exploratory moves are played so that we can learn from states that we wouldn’t have experienced otherwise. This is important because if our agent takes the same route over and over again, it may miss out on strategies that might have looked bad at first, but were much better down the line (insert deep philosophical message).

During each game, we update the values associated with each state in an attempt to make them more accurate. This is done by adjusting the value of the last state we’d visited with respect to the resulting state. The following equation makes this clear.

For an action a at state s resulting in state s’, the value V(s,a) is updated by

where is a hyperparameter4 called the step-size parameter. The step-size parameter greatly affects the learning and convergence rate.

This method (a form of temporal difference learning) converges over time if an appropriate value is selected. The resulting set of values is referred to as the optimal values

and the set of moves the optimal values dictate the optimal policy Q*.

As you can see, this reinforcement learning approach to the game resulted in an agent which is able to learn the game pretty well. The agent can not only find the best action in a given position, but can also apply foresight. This ability to apply deep foresight is what makes reinforcement learning not only useful in games, but also in real world applications such as supply chain logistics and process control.

Conclusion

Reinforcement learning is a computational approach to solving problems with clear goals by interacting with its external environment without the need for any additional supervision. The interaction between a learning agent and its environment in the form of states, actions, and rewards leads to a clean, powerful goal-driven framework.

There exists another method of solving reinforcement learning problems called genetic algorithms. These algorithms apply principles such as evolution and natural selection to solve problems. Genetic algorithms deviate from the methods which will be discussed in this series in that genetic algorithms do not use value functions or learn in a single generation.

Value functions are at the heart of reinforcement learning, and it is what my future articles will be about. I’ll be going through Dynamic Programming, Monte Carlo and Temporal Difference Learning methods soon. But before that, my next post will be about setting up the OpenAI Gym and playing with the CartPole and Atari Space Invaders environments.

Footnotes

[1] Hu, J.; Niu, H.; Carrasco, J.; Lennox, B.; Arvin, F. (2020). “Voronoi-Based Multi-Robot Autonomous Exploration in Unknown Environments via Deep Reinforcement Learning”. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. 69 (12): 14413-14423.

[2] Number of legal 7 X 6 Connect-Four positions after n plies, Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.

[3] Dynamic programming can be used to solve reinforcement learning problems. However, they are only useful in cases where the state size is small and complete environment knowledge is available.

[4] A hyperparameter is a value which the programmer has to set on his or her own and these may oftentimes greatly influence a particular aspect of the algorithm.