The OpenAI Gym is a fascinating place. The Gym makes playing with reinforcement learning models fun and interactive without having to deal with the hassle of setting up environments. While you could argue that creating your own environments is a pretty important skill, do you really want to spend a week in something like PyGame just to start a project? No? Well let’s get right to it then.

According to OpenAI, Gym is a toolkit for developing and comparing reinforcement learning algorithms. It supports teaching agents everything from walking to playing games like Pong or Pinball. And it is, to date, the best place to play around with RL. It is easy to use, well-documented, and very customizable. Go to the Table of Environments for a breakdown of all they have to offer. Without further ado, let’s get to work!

Setup

To start working with the OpenAI Gym, we need two libraries:

- Anaconda: This is an open-source Python distribution for data science and machine learning. Anaconda has its own package manager

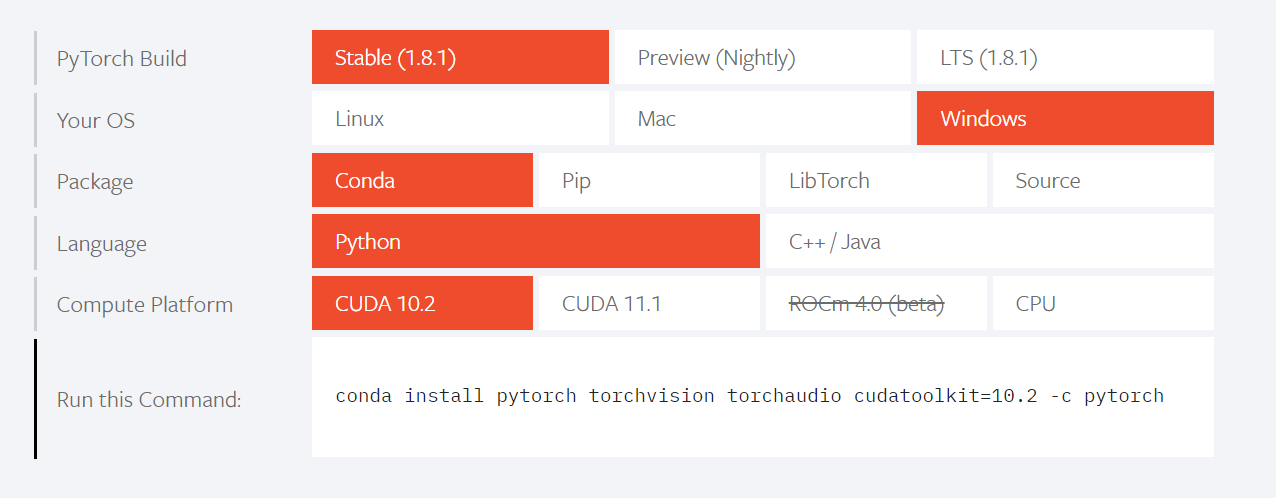

conda, which works alongsidepip. The installation process is simple and the Products page has easy-to-use installers. - PyTorch1: This is an AI/ML library from the Facebook AI Research(FAIR) group. It is similar to NumPy in matrix manipulation, but is more optimized and allows GPU support. Just go to the Pytorch website and select your system. CUDA is for NVidia GPUs, so if you don’t have one or have an AMD GPU (like me), select the CPU option.

Going to the Gym

Setting up the Gym and running environments is a very simple process.

pip install gym

That’s it.

That was Part 1 of the setup. Next we need to install a few modules. Here I will be showing you the Box2D (Lunar Lander) and Atari (All Atari games) environment setups for now.

For Box2D:

conda install swig

pip install box2d

pip install gym[box2d]

For Atari, there are two ways:

pip install gym[atari]

If this throws any errors, use this instead:

pip install -f https://github.com/Kojoley/atari-py/releases atari_py

On Windows systems, you may need to install Microsoft Visual Studio Build Tools (from here).This will be the case if you see any errors involving \atari_py\ale_interface\ale_c.dll.

First Steps

Let’s start with something iconic from the Atari 2600, Ms. Pac-Man. We shall simulate the game here using the OpenAI Gym. Let’s first import the gym library.

import gym

To create an instance of an environment we use the command gym.make("env_name")

env = gym.make("MsPacman-v0")

env.reset()

env.reset() initializes the environment to a default value.

To see the agent play the game, we render the environment.

env.render()

>>>True

As you can see, Ms. Pac-Man starts with 3 lives and has an initial score of 0.

We then make our agent Pac-Man perform a random move.

action = env.action_space.sample()

new_state, reward, is_done, info=env.step(action)

Let’s break this down. The action_space consists of the possible actions that can be done in an environment. sample() randomly chooses an action. Here we can see this:

env.action_space.n # Number of possible actions the agent can take

>>> 9

env.get_action_meanings() # List of actions, NOOP means no actions.

# All actions correspond to their own numbers eg. 0 -> NOOP, 1-> UP etc.

>>> ['NOOP', 'UP', 'RIGHT', 'LEFT', 'DOWN', 'UPRIGHT',

>>> 'UPLEFT', 'DOWNRIGHT', 'DOWNLEFT']

env.action_space.sample() # Randomly selects a number. 2 -> RIGHT

>>> 2

env.step(action) is our agent taking the specified action. new_state refers to the new position of the environment after our agent has taken a step. reward is the immediate reward from the action; is_done is a boolean variable which signals the termination of the game; and info sometimes contains extra information. In this case:

print(info) # Number of lives left

>>> {'ale.lives': 3}

If we put all this in a while loop, our agent performs decently.

is_done = False

while not is_done: # Loop until game ends

action = env.action_space.sample()

new_space, reward, is_done, info = env.step(action)

env.render()

env.close() # Close the window

Here is my simulation of running the game with random actions(Notice how the agent moves erratically).

Random Search Policy

As we can see above, randomly letting an agent do whatever isn’t really learning. Every now and again, however, the agent might find a good action. Given sufficient time (and luck), we might find the best set of actions; i.e., the optimal policy. This is done by repeating the process multiple times and selecting the set of actions with the highest reward. This happy-go-lucky approach is called the random search policy.

To demonstrate this policy, we will look at a classic reinforcement learning task: CartPole. The job is to balance a pole on a moving cart for as long as possible. The pole falls if its angle increases by more than 12 degrees from the vertical, or if the cart moves 2.4 units from the origin. We are rewarded by 1 each timestep the pole doesn’t fall. The environment terminates after 200 timesteps.

Let’s first initialize the environment.

env = gym.make("CartPole-v0")

state = env.reset() # Initialized to a random state

print(state)

>>>[-0.01926058, 0.03751507, -0.03824496, 0.00780216]

The 4 state values represent the cart position (Range: -2.4 to 2.4), cart velocity, pole angle in radians(Range: -0.209, 0.209) and pole velocity at the tip respectively. Also there are 2 actions, move left or move right.

num_states = env.observation_space.shape[0] # Number of states: 4

num_actions = env.action_space.n # Number of actions: 2

num_episodes = 1000 # Number of trials

Let’s first run a trial:

# Initializations

state = env.reset()

total_reward = 0

is_done = False

values = torch.rand(num_states, num_actions)

print(values)

>>>tensor([[0.4365, 0.6748],

[0.6149, 0.6175],

[0.9683, 0.0224],

[0.6787, 0.0233]])

is_done is a variable that is used to check whether the episode has terminated. We don’t know how much emphasis we should put on one measurement in the state, so we randomly assign importance. The PyTorch word for matrix is tensor.

while not is_done:

state = torch.from_numpy(state).float() # For matrix multiplication

# Index with highest value from 1x2 matrix is selected

action = torch.argmax(torch.matmul(state, values)).item()

state, reward, is_done, info = env.step(action)

total_reward += reward

print(reward)

>>> 24

from_numpy() converts the state from a NumPy array to a Torch Tensor and float() ensures no precision is lost.This is done to prevent incompatibility errors. The next line is the most confusing here. For this let’s print everything.

print(state) # a simple 1x4 matrix

>>> tensor([ 0.02783453 0.04837403 0.02878761 -0.00395011])

print(values) # a 4x2 matrix

>>>tensor([[0.4365, 0.6748],

[0.6149, 0.6175],

[0.9683, 0.0224],

[0.6787, 0.0233]])

# The resulting multiplication product will be 1x4 * 4x2 = 1x2

weights = torch.matmul(state, values)

print(weights)

>>>tensor([0.0671, 0.0492])

After multiplication we get the values 0.0671 and 0.0492. These are the weights of the actions. The next step is simply choosing the action with the higher weight.

action = torch.argmax(weights).item()

print(action)

>>> 0

As the 0th index had the higher value it was selected by torch.argmax. .item() is a PyTorch method that converts tensor(0) to 0, i.e. converts a 1x1 matrix into a value.

We convert this into a function for reusability.

def run_episode(env, values):

state = env.reset()

total_reward = 0

is_done = False

# _ = True

while not is_done:

state = torch.from_numpy(state).float()

action = torch.argmax(torch.matmul(state, values)).item()

state, reward, is_done, info = env.step(action)

total_reward += reward

return total_reward

We now run the random search process. Since we don’t know what the best set of values are, we just keep trying with random values until we hit the jackpot.

best_reward = 0

best_values = None

total_rewards = []

for episode in range(num_episodes):

values = torch.rand(num_states, num_actions) # Random values

reward = run_episode(env, values)

# Keep track of the best rewards and values

if reward > best_reward:

best_reward = reward

best_values = values

# Keep track of all rewards for comparison

total_rewards.append(reward)

print(f"Average reward, {num_episodes} iterations: {sum(total_rewards) / num_episodes}")

>>> Average reward, 1000 iterations: 48.42

print(best_reward)

>>> 200

The average reward over a thousand iterations is rather low, while the best reward is 200, the maximum. If we run the episode 200 times with the best values, we get the following:

eval_num_episodes = 100

eval_total_rewards = []

for episode in range(eval_num_episodes):

# Doing the same thing here

reward = run_episode(env, best_values)

eval_total_rewards.append(reward)

print(f"Average reward, {eval_num_episodes} evaluation iterations:",

f"{sum(eval_total_rewards) / eval_num_episodes}")

>>> Average reward, 100 iterations: 158.86

This average reward is a lot higher than randomly selecting values2.

There is a very easy improvement to this algorithm which I’ll leave as an exercise. Instead of randomly selecting values each time, we can start with 1 matrix of random values in the beginning and updating it over time. This update can be in the form of adding some scaled random noise (say scaling factor * torch.rand(num_states, num_actions)) and we only update when the score improves. This method is known as gradient ascent.

Conclusion

The OpenAI Gym provides a quick and simple way for everyone to get into RL. Unlike other hot AI fields like computer vision or natural language processing, a good portion of foundational reinforcement learning does not require any form of GPU support. In all subsequent articles I will stick with PyTorch, but you can feel free to do the same thing with NumPy. It is supposed to work, albeit more slowly.

There are a large number of Atari games that can be simulated in the Gym. A full description and simulations can be found here. The Ms.Pac-Man environment is simulated above. Sadly, the game is too complex for something like Random Search (or even Gradient Ascent for that matter) to get correct.

Random Search is a very basic way to solve a reinforcement learning problem. One could argue this isn’t even really learning, and to that I’d have to agree. Random search and gradient ascent work on simple environments like CartPole, but would absolutely tank in an Atari game. My next post will be on Dynamic Programming RL, a very powerful method that always converges to an optimal policy.

Footnotes

[1] While I won’t be explicitly going through PyTorch for brevity, I will explain the functions I use as they come up. Some level of experience with matrices and NumPy is inevitable.

[2] The value may vary from anywhere between 140 and 190 as the environment is always initialized randomly.